The MTP 2020 Amendment Bill: anti-rights subjectivity

In India, abortion has been allowed in limited circumstances since the Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act 1971 was passed, creating an exception to the offence of abortion under the Indian Penal Code, 1860. The law’s primary purpose was population control and family planning and it lacks a rights-based framework. The law is doctor- centric and over-medical-izes abortion, stripping pregnant persons of their right to bodily and decisional autonomy and vesting the decision to abort with the doctor. On 17th March, the Lower House (Lok Sabha) of the Indian Parliament passed the MTP Amendment Bill 2020, a new set of amendments to this nearly five-decades-old law. Sadly, this Bill fails to measure up to the existing reproductive rights jurisprudence developed by the Supreme Court of India and the fundamental rights to autonomy, bodily integrity, and privacy.

In this commentary, the authors build on earlier analyses in the media and adopt an inter sectional lens to highlight critical gaps in the proposed amendments. The commentary represents the coming together of a broad-based coalition of stakeholders willing to build consensus on contentious issues that have sometimes divided movements and constituencies.

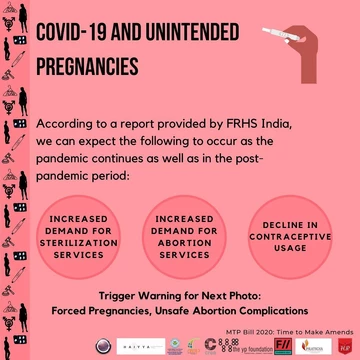

The MTP Act 1971 sets the gestational limit for abortion at 20 weeks, beyond which abortions may only be performed, barring a court order to the contrary, when there is risk to the life of the pregnant person. Even within this limit, however, doctors are often hesitant to provide abortion due to fear of investigations and prosecution. This results not only from the criminalization of abortion under the Indian Penal Code, but also confusion surrounding the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (PCPNDT) Act, 1994 and the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act, 2012. These barriers to safe abortion access have resulted in numerous litigations across the country. A Pratigya Campaign study showed that from 2016 to 2019, 194 women petitioned courts seeking approval for abortion; 40 of these were for pregnancies below 20 weeks.

In 2003, the Rules to the MTP Act were amended to conditionally allow certified providers, outside registered facilities, to provide medical abortion (MA) services up to seven weeks. Out of the 15.6 million abortions that occur annually in India, 81% are done using MA. While the greater availability of MA pills has resulted in an increase in access to abortion, the regulatory framework remains poorly implemented. Medical abortion is a safe and non-invasive method. However, the government has failed to ensure that a sufficient number of public healthcare facilities are equipped to provide abortion services; as a result, the majority of abortions are being sought in the private sector. This means an increase in costs, which can be prohibitive for marginalized groups, specifically those already facing barriers to healthcare access due to caste, religion, age and other factors.

The current law reflects hetero normative-patriarchal understandings of family planning as a means of population control, rather than an exercise of reproductive autonomy. The 2020 Bill does little to advance the rights of or recognize the agency of pregnant persons.

First, the amendments do not recognize abortion at will for any stage of the pregnancy, despite evidence that medical abortion is safe and non-invasive. Instead, the Bill continues to require doctors’ approval for abortions and limits the circumstances under which this approval can be given. An important gain from these amendments is the relaxation of the requirement; only one doctor is needed to approve abortions for pregnancies up to 20 weeks, as opposed to the earlier requirement of two. However, the pool of providers remains unchanged. There is a need to widen the provider base and allow for mid-level provision – by AYUSH practitioners, staff nurses, medical officers and auxiliary nurse/midwives – of abortions up to 12 weeks, based on guidance by the World Health Organization.

Second, while the 2020 Bill extends contraceptive failure as a ground for abortion to any “woman or her partner” – as opposed to only married women – the inclusion of the term “partner” suggests that women will still have to cite relational grounds when they seek abortions. This provision will exclude large numbers of single women, especially from marginalized groups, such as sex workers. Additionally, this provision continues to use “woman” and excludes transgender, intersex and gender-diverse persons.

Third, the extension of the gestational limit beyond 24 weeks is available only for pregnant women with diagnoses of fetal anomalies. The foregrounding of such an able-ist and paternalistic framework within which to expand abortion access needs to be interrogated. Eugenic policies have, throughout history, targeted vulnerable groups. Abortion access should be within a framework of autonomy and self-determination, rather than focusing on specific grounds. The Nairobi Principles recognized that there is “no incompatibility between guaranteeing access to safe abortion and protecting disability rights, given that gender and disability-sensitive debates on autonomy, equality and access to health care benefit all people”.

Furthermore, the amendments categorize only those whose pregnancies result from sexual violence as legitimate claimants to abortions beyond 20 weeks, thus creating a hierarchy of “victim hood”. They also set the gestational limit for them at 24 weeks. Compelling a person to carry a pregnancy to term is a violation of their right to life and dignity, especially when the mental trauma resulting from the sexual violence is immense, as reflected in the 1971 MTP Act itself.

The 2020 Bill also mandates third-party authorization for abortions post 24 weeks through the constitution of Medical Boards with at least five experts. Most specialists are concentrated in urban areas and, hence, seeking authorization from these Boards will result in substantial costs as well as delays for marginalized persons, especially those in rural areas. As we noted earlier, this will disproportionately impact groups such as Dalits, and Adivasis, for whom the structures of caste and class already act as barriers to accessing quality healthcare.

Finally, the confidentiality clause in the 2020 Bill allows disclosure of the pregnant person’s details to persons “authorized by law”, which violates the right to privacy.

Conclusion

The Indian Supreme Court has developed strong jurisprudence on reproductive rights. In the landmark privacy judgment, Justice Chandrachud stated that reproductive choice should be read within the personal liberty guaranteed under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. The MTP Amendment Bill 2020 also articulates the need to ensure “dignity, autonomy, confidentiality and justice for women who need to terminate pregnancy”. However, the amendments do not translate into an actual shift in power from the doctor to the person seeking an abortion. Thus, abortion remains a conditional provision and not an absolute right.

The long journey of legislating access to safe abortion that started in 1971 can truly be said to conclude only when India decriminalises abortion. Meanwhile, there is a need to create a rights-based legal framework on abortion that is in line with constitutional values and India’s international human rights law commitments. The struggle continues – for a law that upholds the rights to equality, autonomy, bodily integrity and privacy; and for one that can transform the ecosystem within which people can exercise their full range of reproductive rights, and particularly their decisional autonomy to seek abortions.

This article has been written by Dr Suchitra Dalvie, Alka Barua, Rupsa Mallik Anubha Rastogi, V. Deepa, Dipika Jain and Manisha Gupte and was drawn from the deliberations during the MASUM and Pratigya Campaign consultation in March 2020.