Reproductive Rights: One Glove Does Not Fit All – Part 2

Traditional Barriers:

The Indian middle classes have been quick to welcome the change in economic progression, and there’s a surge in the number of middle-class students entering professional courses, or taking up well-paid jobs. But while education should equip men and women to question old traditions and religious restrictions on sexual and reproductive freedom that has not been the case. Old patriarchal ideas of marriage, property, and women as wombs persist, and even if young girls are allowed to fare better than their mothers or grandmother, they are still subjects of gender discrimination.

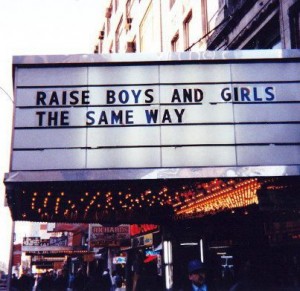

“The status of women is best understood, when you compare them with boys in their own cohort,” said Dr. Manisha Gupte, the co-convenor of Masum in a recent interview with ASAP. “When a family is poor, and food is sparse, a girl might get less food than her brother. When those basic amenities are met with, both the girl and the boy will enjoy a sumptuous meal. But her education might be restricted or her whereabouts monitored.” She points out, that most women are still forced to get married at a young age, quit their jobs to raise families, and are not given the option to choose the number of children they want to have. “In more progressive families, they might allow her to get a masters before she is married, but will probably not send her abroad, even if they send her brother. In other families, they will send her only after she is married or with her brother. In any case, she enjoys less freedom than a boy.”

“The status of women is best understood, when you compare them with boys in their own cohort,” said Dr. Manisha Gupte, the co-convenor of Masum in a recent interview with ASAP. “When a family is poor, and food is sparse, a girl might get less food than her brother. When those basic amenities are met with, both the girl and the boy will enjoy a sumptuous meal. But her education might be restricted or her whereabouts monitored.” She points out, that most women are still forced to get married at a young age, quit their jobs to raise families, and are not given the option to choose the number of children they want to have. “In more progressive families, they might allow her to get a masters before she is married, but will probably not send her abroad, even if they send her brother. In other families, they will send her only after she is married or with her brother. In any case, she enjoys less freedom than a boy.”

As far as abortions are concerned, even educated and working women are not always aware of their rights over their body and their reproductive choices. So, they remain dependent on a male or elderly member of the family . Also, negative attitudes towards unwed pregnancy or pregnancy after widowhood may drive financially dependent, middle class women to seek clandestine, unsafe abortions.

“Women are still subject to distorted views of pregnancy,” Dr. Gupte said. This can to some extent be blamed on the lack of a rights-based approach in the implementation of family planning policies, including safe abortions.

A recent examination of family planning laws in China, points out that a lack of a rights based approach extends to China as well. While there’s been a well-deserved furor over the forced abortions in China, the idea of a woman as a womb has not been openly questioned. Most women in China are still subject to patriarchal norms of marriage, pregnancy and childbirth. Moreover, the forced one-child norm in China, has caused several poor families to kill their female infants, and driven rich families to choose costly methods like IVF, where the sex of the child can be determined and chosen before implantation.

Other Asian countries:

These disparities extend to other Asian countries as well. Guttmacher studies show that while stringent laws in Pakistan restrict the access to safe abortions, wealthy women have been able to avail of services in the private sector, while poor women have often been victims of unsafe abortions. In other countries like Malaysia, where negative attitudes toward abortions have limited the development of centers that provide safe abortions, urban wealthy women have been able to take advantage of the private sector, and clandestine but safe abortion clinics. Poor and rural women are forced to have unsafe abortions, or forced to carry unwanted pregnancies to term.

Dr. Gupte said that there was an urgent need to take into account the actual impact of the capitalistic markets on the empowerment of women, to urge governments to repeal coercive laws and to improve access to health care, so that women can access quality health care, without having to depend on high-cost, private clinics. She also said that every law had to include the needs of women from all walks of life, and provide reproductive options for all of them. “Reproductive rights are part of human rights, and it is not possible without social justice,” she said.

She also said that it was important to take into account the experiences of individual women, and to make sure they were offered the kind of reproductive freedom they needed. “If a woman wants more than four children, she should be able to do that. If a woman wants zero children she should not be questioned about it. The demand for reproductive rights is universal. Every woman wants them, as a part of her right to a life of dignity. But every woman wants something different out of it. One glove does not fit all.”