Meet Savitribai Phule – A Feminist from the 1800s

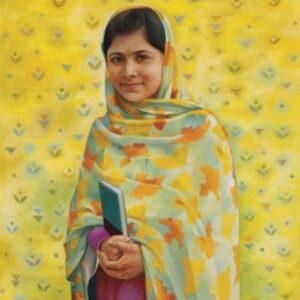

We live in an age of information, and most of us reading this blog can take preliminary education for granted. This is probably why we were all really shocked last year when the Taliban shot 15-year old Malala Yousafzai for defending the right of young girls to education. But if we live in areas where young girls can walk to school without being attacked it is because other young Malalas have braved criticism and danger in their times.

India observed the 180th birth anniversary of one such feminist on Jan 3 — Savitribai Phule. She not only fought for the right to education, but for the right to dignity for widows, unwed mothers, and women with unwanted pregnancies. In the nineteenth century, her work was revolutionary. Here’s her story!

Savitribai lived under the British Raj, and along with her husband Jyotirao Phule was one of the most prominent social reformists between 1847 and her death in 1897. As was the tradition in those days, Savitribai married Jyotirao when she was nine, and he thirteen. She has always had a fascination for words, and was also impressed by Jyotirao’s cousin Saguna, who was a nanny in the house of a British official and spoke English.

At 16, Savitribai joined Saguna and sparked revolution by setting up a school for young people of the lower castes and economic classes. This in those days was taboo. Stories suggest that orthodox Hindu men of the upper classes attacked Savitribai whenever she visited her school. Sometimes, they abused her verbally, and at other times they pelted her with cow dung, rotten vegetables and stones. But Savitribai’s determination never wavered. With her husband’s help, she set up five other schools, and by the age of 19 was an accomplished teacher herself.

Savitribhai led the battle for women’s liberation along several other fronts. As a young wife, she saw that several women her own age were already widowed. Some of them were forced to sacrifice their lives at their husband’s pyre (Sati), and others were condemned to a life of seclusion. Savitribai joined social reformists of her time and worked to efface the stigma against these women, and to incorporate them into society. With her husband, she ran a home for pregnant widows and orphaned children, and took personal care of the destitute women who took refuge in that home.

She soon discovered that women are often stigmatized for unwanted pregnancies. She ran a delivery home for such women, and took care of their abandoned children. Her husband even let one child take on his name, an act that earned him criticism.

Savitribai was a soldier of reform, and she died taking care of women affected by an epidemic of plague. She was one of the only women of the time whose death was reported in a newspaper.

Young Indian women of today owe a debt of gratitude to women like Savitribai who braved stigma. She voluntarily lived on the fringes of her society – an outcast in some ways, because of what she believed in. Yet, it never deterred her from her goal – the advancement of women through education. She was also one of the first women to work hard against misogyny during the period of the British Raj.

Coming back to today, education still remains elusive to young girls around the world. Across Asia, child labour and child marriage rob children of their right to complete basic school education. Without education, these young girls are unable to read and access information about their own bodies and health, let alone about their rights and choices.

While there are several attempts at providing illiterate women information in simplified forms, there is nothing like sending a girl to school and helping her develop the skills to think and form opinions of her own. What we need is for women to come together as a fitting tribute to the Savitribais of yesteryears, and the Malalas of today and support education among women. After all there is only one way to combat misogyny and stigma – education. But to achieve that we first need to protest the stigma against educating young girls.