Bearing the Brunt of Crisis: Women in Conflict Areas

The last decade has seen a drastic increase in the number of people who are displaced or living in conflict zones, and in need of humanitarian assistance. As is the case when it comes to living with vulnerabilities, the lives of women and children, especially young girls, face the brunt of marginalization. In 2016, it was estimated that of the approximately 100 million people who were targeted with humanitarian aid, an estimated 26 million were women and girls of reproductive age.[1] It is perhaps then, unnecessary to underline that the sexual and reproductive health and rights of people living in emergency situations, particularly women and girls, requires urgent attention.

It is a well-known fact that crises exacerbate existing violence against women and girls, and present additional forms of violence against girls and women. The insecurities inherent to conflict situations, and subsequent life as a refugee gives rise to many forms of gender-based violence (GBV), including sexual violence, threats of trafficking, and forced marriage. Further, girls and women are often more greatly affected by both sudden and slow-onset emergencies, and often face diverse sexual and reproductive health challenges. The violence faced by women is further compounded by the fact that these women have limited access to healthcare, and when they do, health care systems refuse to acknowledge the consequences of such sexual violence[2]. As a consequence, in addition to being serious human rights violations, these abuses contribute to unintended pregnancies, and in turn, can lead to high rates of unsafe abortion and maternal mortality. According to UNFPA estimates, three-fifths of all maternal deaths globally, take place in humanitarian and fragile contexts. Of this, between 25–50% of maternal deaths in refugee settings are due to complications of unsafe abortion.[3]

There is an immense need for health systems to enable women to exercise autonomy by providing effective contraception, as well as the ability to terminate unwanted pregnancies legally and safely.

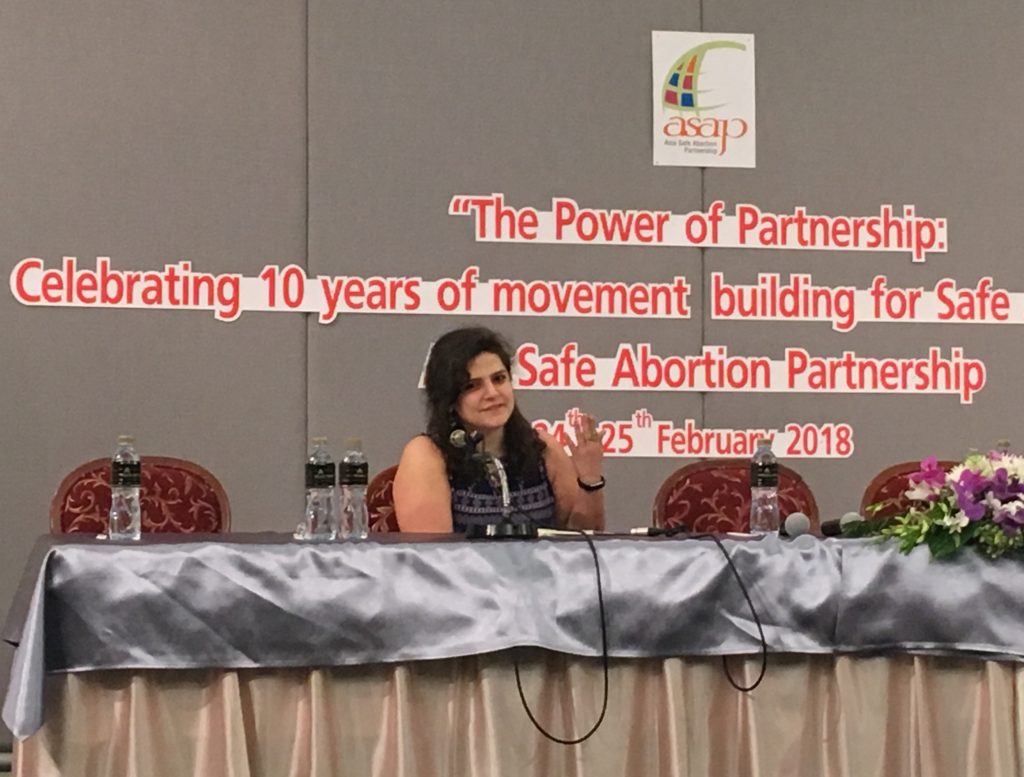

It is this context that our interview with Rola Yasmine, Founder, The A-Project, Lebanon, becomes even more significant. Last year, she had spoken with us about her work with Syrian women who are refugees in Lebanon; we’ve reproduced part of that conversation here:

Can you talk about the inter-linkages between sexual violence and abortion rights in your work with displaced/refugee women?

I think actually focusing only on sexual violence may not necessarily be the only angle to talk about displaced citizens and violence against women. I think to some extent, people want to see more of sexual violence in refugee settings because there’s a demand to have images that pity and victimize women. But there is so much violence against women who are displaced that is not necessarily sexual by nature. I think that institutionalized racism and xenophobia limits refugees’ access to all sorts of basic services, especially for reproductive health and safe abortions and that is also violence against women.

Can you give specific examples of refugee women’s experiences while seeking sexual and/or reproductive services?

Women tell me that they go to pharmacies to get contraception or to get misoprostol and pharmacists harass them not because they want to do abortions but because they are Syrian, blatantly saying “is this really the time for you people to be procreating?” These kinds of statements are not only said by pharmacists but also from physicians, midwives and nurses, and not only Lebanese but also Syrian doctors and midwives of middle-class upbringing.

The educated middle class do not see that even in the middle and upper classes, people have unprotected sex all the time and women become pregnant and have unwanted pregnancies, they just have money enough to cover it up. The lives of people in poverty are just so exposed and so transparent so it’s so easy to point at them and say “wow you guys are really behind.”

Can you talk about women’s experiences accessing abortion?

One woman called us from a refugee camp in the North of Lebanon; she was a widow and had 2 children, one whom had an untreated serious health condition of Hydrocephalus. She re-married thinking that it may help her take care of her children, but the man she married was a divorcee who had a child that he wanted someone to take care of which is why he was looking to remarry. He was physically violent and severely abusive and would keep threatening her with divorce although he gave her nothing in monetary value to her or her kids. She was looking for an abortion, but it was a little difficult and when she finally asked for it she faced resistance. She started taking all sorts of over the counter medication.

While less frequent, there have been callers who have faced sexual violence and rape and calling for post-abortion care. A widowed Syrian woman was raped in a refugee camp and she couldn’t tell anyone about the rape because it was a powerful and violent Lebanese man in the camps. She was worried that if she said she was raped, people may think she was doing sex work.

What is the role played by the International NGOs (INGOs) involved?

Service providers in INGOs asking women if they are married may be a deterrent to care for those who are separated, widowed, unmarried, divorced, and/ or doing sex work. Many women have said that they keep getting told to come to counselling and mental health sessions to talk and re-talk rape that she’s experiences and process it, while they are usually looking for safety from a repeat offender or an abortion if the rape resulted in a pregnancy.

It isn’t surprising that talking to a counsellor isn’t on the top-ten list of needs to many refugees. What is upsetting is that you hear service providers wrongfully presume that refugees reject mental health counselling because of the stigma around the field and it not be seen as a real science – when it’s just seen as a bit of a luxury at this point or foreign practice at any point in their lives.

What do you see as the role of The A Project in this context?

The A project works on giving information about reproductive and sexual health as well as referrals subsidized or free services. We work on politicizing the conversation around sexuality and gender, whether with local activists or healthcare providers.

Part of the A Project really is the launch of a Hotline to talk about all things to do with sexuality and gender so you don’t get a washed down answer on how effective a condom is and its 3% failure rate. But you talk about the politics of how it’s really difficult to negotiate it sometimes, the barriers that aren’t as easy to quantify. So it is to have the conversation within feminist politics and expose medical patriarchy. We also do political sensitization trainings for health care providers.”

We work on producing feminist research and knowledge that responds to the patriarchal hegemony that demonizes and problematizes the agency and autonomy of young women, queer women, refugee and migrant women, sex workers, and gender non-conforming folks.

You can read more about Rola’s work in Lebanon here.

For more about what the A-Project does, follow them on Twitter.

[1] http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/news/srhr-refugees-migrant/en/

[2] https://www.reproductiverights.org/sites/crr.civicactions.net/files/documents/ga_bp_conflictncrisis_2017_07_25.pdf

[3] https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/sowp/downloads/State_of_World_Population_2015_EN.pdf