A Feminist Perspective for Safe Abortions in India: In Conversation with Dr. Manisha Gupte

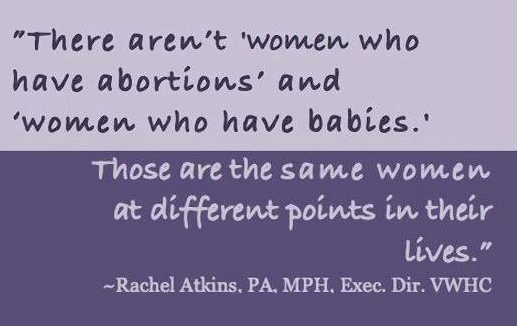

The different contexts within which women undergo abortion need to be understood and appreciated. There is no single monolithic right to abortion. To access the right to abortion, women need to be free of coercion from family or the State, from son-preference and so on.

Manisha Gupte

A Walk Down Memory Lane

It’s been nine years since Dr. Manisha Gupte penned her article, A Walk Down Memory Lane on the ups and downs of the campaign against sex-selection. But, sex-selection still remains a major issue in India, and the campaign still struggles to focus on the core issue: gender discrimination.

Earlier this year, the campaign found champions in the media, the government and in celebrities, and shot to prominence again. Sadly, it unfairly targeted and vilified abortions. As we wrote before, this is not likely to reduce sex-selection, but reduce access to safe abortions, increase stigma, create a black market for abortions, and increase the rates of unsafe abortions.

India has a fairly liberal law on abortions. The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act of 1972 permits women to have an abortion if the pregnancy poses a threat to their lives, has resulted from contraception failure or sexual assault or incest, or presents a risk to mental and physical wellbeing of the woman. In addition, terminations can be done for socio-economic reasons, and in case of fetal disorders. While a single medical practitioner can approve the procedure before 12 weeks, the opinion of an additional doctor is required between 12 and 20 weeks.

Yet, two-fifths of the abortions in India are unsafe, according to the Guttmacher Institute’s estimates. This can be attributed to the lack of access to accurate information, abortion stigma, and a dearth of affordable facilities. Any undue vilification of abortions – as with the campaign against sex-selection – is likely to reinforce these negative attitudes, and multiply these barriers.

ASAP interviewed Dr. Manisha Gupte, and discussed with her the need to separate abortions from the campaign against sex-selection, and to promote it as a reproductive right.

Dr. Gupte identified the need to promote access to accurate information about the MTP act, and its tenets. The MTP act was passed before the women’s movement consolidated in the 1970s, and therefore, it did not get the hype that the Pre-conception, pre-natal diagnosis techniques act (PCPNDT) got in the 1990s. “A lot of people don’t know that abortions are legal in India,” she said. “People got to know about it only through the PCPNDT act,” she said explaining why abortions and sex-selection were intricately connected in the minds of people.

Along with campaigns to educate people (both in the community as well as in the media) about the MTP act, she calls for the need to analyze the Act from a feminist perspective. The government of India introduced family planning in 1952, and passed the MTP act in 1972, both before the consolidation of women’s movements. While these policies were meant to help women gain some control over the size of their families, the policies do not address abortion and family planning as a reproductive right. Dr. Gupte suggests that these acts be reviewed and a rights- based approach included.

But she offers a caveat: the fear of regression. “In the 80s and 90s, we did not want to touch the MTP act because we were afraid it would lead to restrictions,” she said. “Such a fear still remains. The climate is tipping toward violent identity politics,” she points out, “with events like breaking clinics, rampaging over a cartoon.” Dr. Gupte instead suggests a closed-door conversation between progressive groups, capable of offering views that advance our understanding of abortion as a right. Such a consolidated opinion could then be integrated into campaigns for women’s health and women’s rights, including those against sex-selection and coercive family planning laws.

The inclusion of a feminist perspective will help fight gender discrimination much better than “the flowery jingles about boys and girls.” Such views will culminate in social transformation, and help change the ways in which we view gender, or discriminate against it, she said.

“It is important to understand that sex does not make a difference in people’s lives, gender constructs do,” she said. “People should know that gender is not sex. Religion, ethnicity, caste, class and so on construct gender. Women are not homogenous, and don’t have homogenous needs.” In the end, she hopes that the inclusion of such strong visions will lead to social transformation, and slowly erase gender discrimination, without affecting women’s rights to abortions.

Dr. Gupte says that there are economic reasons behind the current drive to find a quick fix to sex-selection by restricting abortions, and selectively criminalizing it. With large funds being directly towards these campaigns, she said that the people involved felt the urgency to demonstrate their results. “They believe that all advocacy has to end in policy change,” she said, “So they want a law passed. But what seems like a good reform now could be very hurtful a few years down the road.”

Instead she pressed for the need to strictly implement laws that were already passed: like the anti-dowry act, or the child marriage probation act, or the inheritance act which allowed women to take charge of their lives. This she believes would empower women and effect social transformation. “I sound like a broken tape,” she said, “but it always culminates in social transformation. There are no short cuts.”

Follow this blog for more from Dr. Gupte.

Also, do read A Walk Down Memory Lane.